Compositor, pianista, autor

O.P.A MIA

1987-1989

Opera, for chamber orchestra, choir, two singers and two actors.

Music and text: Denis Levaillant.

Directed by: Philippe Nahon.

Stage Director: André Engel.

Set: Enki Bilal.

Sound broadcasting: Marc Piéra.

Lights: André Diot.

with:

Sunny Cash, God of Money, bass baritone: Vincent Le Texier

Sphinx, Goddess of Truth, lyric soprano: Claudine Le Coz

He, a golden boy: Yann Collette

She, a newscaster: Irina Dalle

and

Ars Nova - Musiques en Scène, Ensemble instrumental national du Poitou-Charentes et de la Rochelle.

Sur bande les choeurs de Radio France, direction Michel Tranchant

et les voix de Jany Gastaldi, Jerry di Giacomo, Anouk Grinberg, Michel Raskine, Robert Sireygeol.

Prise de son: Madeleine Sola assistée de Cyril Becue,

Traitements numériques réalisés à l'INA-GRM.

An analysis by Gérard Condé

Can an opera resemble a takeover bid? Only to the degree that the words of Love occasionally evoke those of the stock market: does one not speak of a love being bankrupt, with someone who was not a "good deal"? Or of "winning" (or "losing") someone's love? Of being "highly rated? To the point that a lovers' dinner can sometimes be mistaken for a brokers' luncheon. Or vice versa. In short, feelings are business!

The language of the stock market is a language of initiates. For the uninformed reader of the financial pages- or, even more so, for the radio listener- the recurrence of the same terms, varied in their presentation or mixed with unknown words, gives this language an incantatory, magical value, as much as the figures, with their mysterious implications, recall the sacred dimension of numeration. Knowing that, for quite some time now, money, through various complicated manipulations, is tending to become a fiction for financiers themselves, and that much more of it circulates through accounts than is produced by the central banks of all the States in the world, its value is becoming as chimerical as that of glory at the time when, in Baroque opera, it was contrasted with love; so that one will not be surprised to see, in O.P.A.. Mia*, money and love confront one another. Denis Levaillant, who is doubtless one of the rare composers capable of explaining in two words what is represented by a swap, admits to being extremely curious about columns concerning financial operations, but it is nonetheless to lovers - the "true initiates"- that he secretly dedicates his opera, and not to bankers.

*Translator’s note: O.P.A.. is the abbreviation for the French term offre publique d'achat meaning 'takeover bid' or 'tender offer'.

The parallel with Baroque opera, attempted as regards the particulars of the subject, is not as audacious as it might seem, insofar as Denis Levaillant has quite obviously found in it a source of inspiration more fecund than in what might be called the avatars of Wagnerian drama, wherein the action and continuous recitative override the suspension of time and vocality. However, under no circumstances is it a nostalgic or backward-looking attitude, but a simple observation that, as regards opera, action is necessary without being sufficient, and that singing must not be limited to the syllabic enunciation of phrases useful for understanding the drama. One of opera's strengths, in relation to theatre, is primarily being able to legitimately stretch the dramatic time, this allowing for giving a few words, repeated for the sake of it, an emblematic value and bringing the characters together through their voices, independently of their bodies, in duets and ensembles.

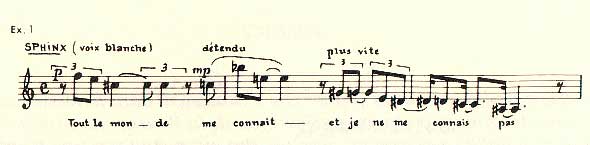

By choosing "long" voices (with a tessitura spanning two octaves), of lyric soprano and bass-baritone, the composer was straightaway committing himself to take them through all the registers:

To these singing characters - Sunny Cash, the god of money, and Sphinx, the goddess of truth - correspond two speaking figures, two humans: a golden boy and a television announcer (who are not their doubles but rather their imperfect incarnation), whose dialogues (or monologues) take the place of recitatives in Baroque opera. Speech (like the recitative) has the advantage of being more directly understandable and allowing for a faster delivery; on the other hand, its relative prosaicness, in an operatic context, seems to destine it to the expression of less lofty passions. To make the most of the qualities of speech without being imprisoned by its limited lyricism was Denis Levaillant's concern when he chose to treat most of the spoken dialogues in music. That is the principle of melodrama, as was defined and experimented with by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and, especially, Georg Benda (1722-1795), whose works so impressed Mozart that he took inspiration from them for Zaide. To what degree the musical background, more or less neutral or active, underlines the words that are superposed on it, or contradicts them implicitly, is what the composer determines with more effectiveness than in the recitative.

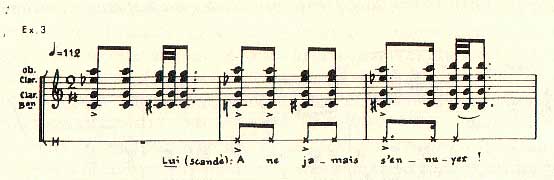

It is generally the orchestra that weaves the backdrop in melodramas; here, it is sometimes the singing choir or the speaking choir, but sometimes also silence, which fully plays its musical role. It goes without saying that, each time, the procedure is implemented in a somewhat different fashion, according to the principle of continuous variation, which governs the entire work. A Latin verse, two duets between Sunny and He, then between Sphinx and She, closely combine singing and speech. In a few passages, the rhythm of the declamation is written down quite precisely, so that either the conductor must pay close attention to the spoken delivery:

or the actor must articulate his text as in Stravinsky's The Soldier's Tale:

The singing choir is not a full-fledged character like the others. Rather, it is more an echo: it reflects, punctuates and marks out the time in the manner of the choir in the Bach Passions, if not the choir in Greek tragedy. The writing, for twelve real voices, is quite dense (a density increased by the frequent recourse to quarter-tones), thus producing effects of mass with relatively modest forces. The speaking choir, limited to the restitution of "realistic" atmospheres (the trading floor at the Stock Exchange, the news broadcast) is the object of an electronic treatment that makes it musical; both are pre-recorded.

The orchestra constitutes a third choir, insofar as it accompanies the voices, enhances or supports them through fleeting doublings, accentuating the sense of certain words with a colour or rhythmic beat, or contrasts them with an explicit refutation by noticeably expressing the opposite of what is being sung or said. Furthermore, it preceded or punctuates: first with an Overture (which depicts "city noise"), then with five interludes, entitled Passages (and a transition: The Between two) and which, placed end to end, could make up a sort of symphonic synthesis of the opera but, in performance, serve as much as interludes as summaries or premonitions.

Little by little, two solo instruments- the clarinet and cello, more or less associated with the female and male characters- take on a more noticeable relief, whereas the orchestra gradually disappears (like the noise of the city would die out), the conclusion being left to the choir alone, as in L'Enfance du Christ. The make-up of the orchestra is unusual in that it combines three quintets: a wind quintet (oboe or English horn, two clarinets - the second doubling on bass clarinet- , bassoon or contrabassoon and saxophone - tenor or soprano); a brass quintet (horn, two trumpets - the second doubling on the bugle-, and two trombones); and a string quintet (two violins, viola, cello and double bass). The flute, tuba and percussion are omitted in favour of the three, more homogeneous ensembles whose proper colour and possible associations correspond to the specific sonority, desired by the composer: fairly taut and vibrant, while excluding neither tenderness nor refinement.

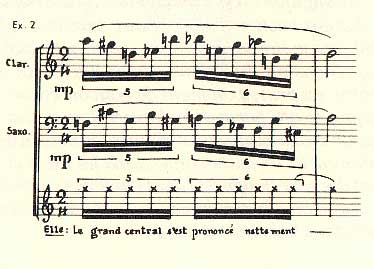

By simplifying things to the utmost, one might say that the orchestral writing alternates fluid counterpoint, in perpetual motion:

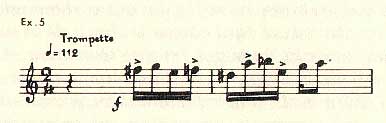

with sequences on the same rythmes, like chorales, in which a sole beat governs all the instrumental parts; a characteristic example is the fatal dance motif that recurs throughout the work, recognizable more on account of its irregular accents than its notes:

The synthesis between counterpoint (horizontal) and harmony (vertical), is achieved in the passages where, without being able to elucidate the harmonic pillars, one has the fairly clear feeling that the various instrumental lines form auxiliary notes round the main, underlying notes. Sometimes there is only a mother note: a very low sound, for example, of which one hears only the playing of remote harmonics (up to the twenty-third) compressed over five or six octaves, that the instruments unfurl in arpeggios. We are then far from the consonance of the first harmonics (G-B-D-F-A, for example, that the ear perceives easily, and form the chord on which Stockhausen built Stimmung), and he brings numerous quarter-tones into the scale of these harmonics but, in some ways, one remains in the sphere of natural resonance, even though that might hardly seem to be the case.

That said, in the course of the work, one encounters "classified" harmonies that are perfectly integrated into the atonal language of the whole. Either they go by very quickly, and their consonance contributes to the sonority, or they are used for their expressive power or, more simply, to enrich the harmonic palette, facilitating the integration, here and there, of fleeting winks at tonality (hence the song Les chevaliers d'antan).

Up until now, there has been hardly any mention of what constitutes the very flesh of opera: the arias and duets. It is that, structurally, they are the keystone and thus form the summit of the edifice. An aria, as we know, is distinguished from a recitative by the presence, more or less noticeable, of repeated elements. Given that repetition generates variations in "serious" music, it follows that repetition and variation enter, to equal degrees, into the composition of an aria. In opera seria, the succession of arias built on an almost immutable model (aria da capo), but each endowed with a particular character ensuing from situations as precise as they are stereotyped, obeyed, overall, this double principle of repetition / variation.

In his opera, Denis Levaillant has taken up and refined this procedure in such a way that, everything or almost everything, be both repeat and variation. Thus Sunny Cash's second aria (‘Le cours? La cote? Le taux?’) appears to be a development of the first, whereas his third ( ‘J'ai tout perdu’) is an obvious imitation of the previous ones. Common to these three arias, amongst other things, is the exclamation that is meant to be reassuring My name is, an exclamation which, meanwhile, had slipped into the duet with Sphinx in response to Sunny's question: ‘Who are you?’. Similarly, Sphinx, in her first aria, had repeated certain words from Sunny's opening aria (‘Le sang de l’argent'). Much later on, this aria of Sphinx's (‘J'étais suspendue’) will be treated as a duet.

These are only examples, chosen amongst those which can be most easily spotted, to give an idea of the internal way in which the score's thirty-six successive numbers are linked to each other, which match and complement one another as the work goes along. When listening, it is doubtless worthwhile to be able to make oneself attentive to these echoes; which are more or less explicit, but in no way is this a sign-posted route, and it is more important to feel these things intuitively than to study an inventory of them. For it is not the abstract concern of musical form for its own sake that guided Denis Levaillant in this way so much as dramatic effectiveness. Similarly, one ought not look for the difference in vocal writing between the roles of Sunny Cash and Sphinx elsewhere than in a characterization design of the characters. For one, broad, determined intervals:

For the other, elusive slidings by quarter-tones:

Nonetheless, even though both vocalize, Sunny Cash is not merely what he would wish to appear; without that, could there be this inversion which is the work's very motivating force? Behind the sham assurance and those repeated words (which He overuses in an even clearer way), there is that flaw into which Sphinx's revealing interrogations work their way.

All opera is a wager and, in a way, a take-over bid.

Gérard CONDÉ

April 1990

Translated by John Tyler Tuttle

Working with Enki Bilal

The most powerful moment of my collaboration with Enki Bilal for O.P.A. Mia will certainly continue to be the day when, the set finally completely assembled (at the Théâtre de Gennevilliers) and the sound system roughly arranged, we heard the first effect, the first mixing of sung voices in the [spatial] volume.

Then we saw we had not been mistaken—that there was a profound connection between his universe and mine. The music had found its image, this transformed, anticipatory reality that I was seeking.

When I broadcast Speakers* at Radio-France, one of my colleagues told me that it made him think of comic books. "Careful, now, that's not a criticism - let's be quite clear on that: good comic books!" The way intellectuals approach comic books today is a bit the way 17th-century letters greeted the nascent novel - a slightly disdainful respect for "something" not yet a listed art form. It's true that comics range from insipid fanzines to admirable graphic work by artists like Bilal. But doesn't today's music also range from the thin home-made soup concocted on the all-purpose synthesizer to the introspective craftsman's art still necessary for composing? And, with those same intellectuals, don't we find the same suspicion of authenticity vis-à-vis musical genres currently considered "minor"? Here, I'm primarily thinking of music associated with the image, a new art of today corrupted by merchants under the term "film music".

Not so long ago, what Enki creates was still being designated as "illustration". The example of our work on O.P.A. Mia strongly refutes that category. My characters existed; the roles were written, the music copied out - Yet there lacked a dramatic characterization. I can say that Sunny Cash, god of money, and Sphinx, goddess of truth, did not come into being until the day Enki agreed to make the "image" of my oper - his vision of gods lost in the urban underground from La Femme Piège precipitated mine. In this case, who is illustrating what? Enki is not a stage designer either. You don't work with him endlessly discussing dramaturgy, you don't constantly keep going back and touching things up. He gets closer, through sensibility. He's a Cat who doesn't make a lot of ruffs. Through O.P.A. Mia, he continued his work. Like a painter.

For fifteen years now, I've been putting on shows with my music and I've carried out a number of works in collaboration. The most efficient practicality has always been the fruit of encounters where everyone remained master of his or her universe. However, habit would have it that art, putting itself at the service of a common purpose, goes astray.

I am betting that the distance I spoke of above, and which touches on the idea of the function of art, will fall one day, all by itself.

I will go so far as to bet that, in the 21st century, the idea of an art that serves no other purpose than itself will give our grandchildren a good laugh - design, image-music, narrative graphics (rather than comic book?) will dominate the market. In the meantime, I am firmly determined to continue exploring my polyvalence (music as performance art), which allows me to meet all-rounders like Enki (who has more of a tendency to carry out his work on numerous supports). I thank him for having travelled a bit with me - here these images, which provide the framework for an encounter, come back: Enki's feeling drawn by my orchestral scores ("I'm jealous of this format"), his constant attention to the entire production crew of the show, his preciseness on the hues during the lighting adjustment, his solid presence facing the media in Avignon - and having accepted to put his graphics into three-dimensional form for the first time, on a theatre stage, for singing my music there.

Denis Levaillant, 20.09.1991

*A radio poem from which O.P.A. Mia was born

An interview with Alain Corneau, film director

O.P.A. Mia, Denis Levaillant's opera, directed by André Engel with sets and costumes by Enki Bilal, was given its first performances at Avignon this summer, to mixed critical reviews and an enthusiastic audience response.

In Denise Luccioni's presentation in our previous issue, she wrote: "It is likely that Engel et Bilal, marked by a sort of warm hyperrealism, pull O.P.A. Mia, for the better, towards a cinema in flesh and blood".

We thought it would be interesting to have the opinion of a filmmaker. Alain Corneau was in the hall and agreed to speak with us about this and that.

Alain Corneau: I had two reactions in seeing O.P.A. Mia.

The first was one of emotion before a pure spectacle, telling myself it was one of the first times that I saw a sort of un-solemn confrontation courageously conducted between what is called spoken theatre and music. The very simple division between the gods, who sing, and the men, who speak, seemed a very good idea to me. Moreover, Engel staged it quite well, and from that moment I felt an emotion, yes, a highly personal emotion on this type of very simple confrontation, which haunts us all, between reality and lyricism.

That, in my opinion, was carried through to a successful conclusion, something that has rarely been done. There has never been this kind of courage to confront actors and singers at the same time, placing them on two different levels but with a passageway from one to the other. In this sense, I think that Enki's set was quite strong, because it is very "comic book"-like, very lyrical and, at the same time, hyperrealistic, fully participating in this combat, which is something eternal in occidental theatre. In other civilisations this was achieved in a more traditional manner, but with us it is still in question.

That is something that interested me quite a bit. I found it handled honestly and sincerely and think it's in the libretto.

- What did you think of the libretto?

The libretto, the very quality of the libretto - there's not much I can say about it, first of all because I'm not a critic, and then, from the moment you block on those words, it's not up to me to make a literary or intellectual judgement. For me, an opera libretto is not something you can separate from the whole. Just as a screenplay can't be criticized as such.

- And your second reaction?

My second reaction - what enabled me to amuse myself in addition to a certain emotion - is that I have a passion, which is Baroque opera, and I here I found, put back on stage, the whole play of mirrors, correspondences, shams, resemblances, plays on reality and with "clichés" all that amuses me enormously in classic traditional French Baroque opera - Rameau & Co.

You asked me about the quality of Levaillant's libretto. But who would criticize a Rameau libretto?

The real question was: does this text carry the music, does the music carry the text, and is the impression of illusion in the Baroque sense, carried through? Well, as far as I'm concerned, in O.P.A. Mia, I saw a sort of Baroque temptation that amused me. It must come from Levaillant, who is not in the lineage of the institutional serialists (who are, for me, a real horror and who form a "sect") so that he found a rather original show idea. He puts into play very contemporary, well-known data that are clichés of our 'journalistic' life. He makes of it a combat between men and the gods, and it's true that French Baroque and Baroque opera - I repeat: French - were obsessed with this dualism.

One thing you also find in O.P.A. Mia is there are no arias - only recitatives. That interests me a lot, because the aria-recitative dispute was at the origin of a divorce and a standstill in French opera of the period. Even Rousseau said it was barbarian music, that it took harmony and arias, arias like the Italians and Germans wrote. And Rameau wore himself out saying there was another way to make music, which was the recitative, which meant setting every word to music but not necessarily melody. In O.P.A. Mia, I found these same issues - there are approximately the same questionings, and I think Denis Levaillant's marginal side allows him to see things in a healthier way, in tradition and in a certain modernity of tradition.

I think that today, modernity is the return to this music.

- What did you think of the electroacoustic part? Of the idea of installing loudspeakers round the set and even in the hall to play the tapes, mixed choirs and city noises?

This kind of accumulation plays and plays quite well. I think Levaillant was right in using a maximum of elements. This electroacoustic music brings to the choirs - which are not conceived as traditional opera choirs- their additional anguish. I think that was the aim, more or less. There, it's true, it fit well. And it fit Bilal well. There were several moments when one had the impression of being in a comic book, which is no mean feat. For too long, too many directors have been influenced by the cinema and less by other forms such as painting, comic books- the pictorial forms of today. There, certain moments were quite close to Enki's drawings, not simply the choires, but the positioning of the red dress, the lighting, which was quite amazing' We avoided smoke- I would have put some in and I would have been wrong. I think that was a brilliant little stroke on the part of André Engel, and it lent nobility to the show.

So, it's a production that breaks the moulds, in a way- it doesn't refer to any school or family. It is kind of an orphan and therefore a bit freer.

I'm easy to please. When I'm enjoying myself, I get interested and then I'm happy.